A SURVEY on the mental health of Australians that was expected to be done in 2017 won’t be funded, a government spokesman has suggested.

Many thought the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, which was done in 1997 and 2007, would survey residents again in 2017.

But in response to inquiries from news.com.au, a spokeswoman for the Federal Department of Health said “the survey was not designed or scheduled to be held every 10 years”.

The move has worried Melbourne University Professor Patrick McGorry, who says we need better data on which to inform policy.

Prof McGorry said the survey should actually be done every five years, not every 10 years.

“This is a serious enough issue that it should be done on a regular basis. The data we currently have is inadequate,” he told news.com.au.

Opposition ageing and mental health spokeswoman Julie Collins told news.com.au the survey provided an important evidence base about the prevalence of mental ill health and provided valuable data for further research and service delivery.

“We are concerned the Government is not funding this important data gathering exercise,” she said. “It is Labor’s strong view the survey should not be further delayed or postponed as this data is needed.”

But the department spokeswoman said it could get data on suicide from other sources.

“The Department makes use of a range of population survey data to inform its work and has ongoing discussions with the ABS on mental health data issues,” she said.

She said the annual ABS Causes of Death survey provides a range of data on suicide, the AIHW publishes frequent updates on health services, including mental health services and that other more localised collections like the Primary Health Networks could be used for particular service provision purposes.

News.com.au has been highlighting men’s mental health issues as part of its campaign The silent killer: Let’s make some noise in support of Gotcha4Life and Movember.

Prof McGorry has been announced as the chair for a potential royal commission into mental health, which Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews announced would be funded to the tune of $13.2 million if Labor was re-elected in November.

“More than 3000 Australians take their own life every year,” Mr Andrews said in a statement.

“Imagine what we’d do if 3000 people were getting gunned down on the street in this country?”

Prof McGorry, a former Australian of the Year and campaign patron for Australians for Mental Health, has welcomed the prospect of a royal commission but there’s no guarantee it will go ahead as the Liberal party has not committed to it.

Federal, state and territory governments are already putting in about $9 billion a year into addressing mental health — equivalent to $1 million per hour. Despite this substantial funding, 3128 people died from suicide in 2017, an increase of 9.1 per cent from 2016.

What Australia is doing is obviously not working.

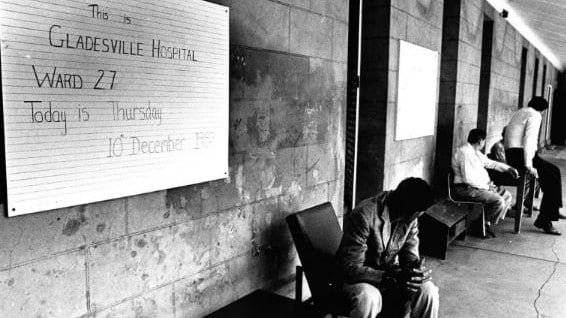

“We need a complete redesign of our system,” Prof McGorry said. “Before we had big asylums located in tranquil settings but we have reduced the number of beds by a factor of 10 and crammed them in acute hospitals.”

In more recent times, psychiatric units were built wherever there was space — over hospital carparks or crammed in small spaces, like the zone between two buildings, “like an afterthought”, Prof McGorry said.

The old Gladesville Psychiatric Hospital. Picture: David MottSource:News Corp Australia

Psychiatric hospitals used to be located in leafy grounds. Picture: Bob Barker.Source:News Limited

“We got rid of the old asylums in the 1990s but we crammed a small number of beds into acute hospitals instead.

“There was no thought put into the design or whether they would work for people, most were done on the cheap and they’re just as disappointing as the wards in the old mental hospitals.”

Now Australia’s suicide rate is on the rise and there are increasing calls for change to how mental health is treated.

Mental illness affects about 4 million Australians and every day eight Australians take their own lives.

Prof McGorry, who is executive director at Orygen, the National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, said Australia was quite innovative in the mental health space, developing programs like headspace, which is aimed at young people, but it was not good at scaling these up and making these programs available to everyone, in the same way that treatment was for conditions like cancer and heart disease.

The World Health Organisation noted in 2013 that no country in the world could say its services were reaching all those in need.

“When it comes to equity in health care, Australia is just as bad as any other country,” Prof McGorry said. “If we can’t change and invest more heavily in expert care, people will continue to die premature deaths.

“We could get much better levels of recovery from mental illness and productivity. It is possible but currently there’s a huge waste of human potential.”

[“source=livemint”]