“Do you want to go viral today?” Matt Jackson asked his younger brother, Nick.

It was a loaded question. The easy answer, the usual answer, was yes. Going viral is a large part of how Matt and Nick, the tag team better known as the Young Bucks, revolutionized the wrestling business and became the most lucrative act outside of WWE.

On August 8, 2015, the brothers were working one of their smallest shows of the year, a local event in Baldwin Park, California, when Matt had an idea. Hours before the show, the 31-year-old noticed the ring announcer’s son, a boy named Luke who was celebrating his ninth birthday, running the ropes and taking bumps far better than any kid his age ought to be able to.

What if we…

“No,” Nick told Matt. Nick, 27, is four and a half years younger than Matt. He’s quieter, more deliberate—the old soul in the family. It wasn’t that he objected to the plan, per se, it was just that it didn’t exactly jive with their sensibilities: Matt and Nick Massie, the men behind the gimmick, are each married fathers of two children—straight-edge sons of a minister who say a prayer before every single match.

Read More: An Inside Look at WWE’s Financial Empire

Nick was concerned about the optics. Nobody in pro wrestling is parsed more thoroughly than the Young Bucks, because no one else has so thoroughly fused the in-ring product—the act of wrestling—with the sport’s other trappings: entrepreneurship, internet rumor mongering, backstage innuendo. All it would take is one person seeing things out of context, and this could look very, very bad. Then again, a stunt like this would most certainly get people watching.

Which, of course, was the rub. More people watching meant more followers on Twitter, more subscribers on YouTube, and, most importantly, more merchandise sales, which form the bulk of Matt and Nick’s income.

So, Nick changed his mind. He did want to go viral after all.

“OK,” Matt replied. “Then we’ve got to kick the kid in the face.”

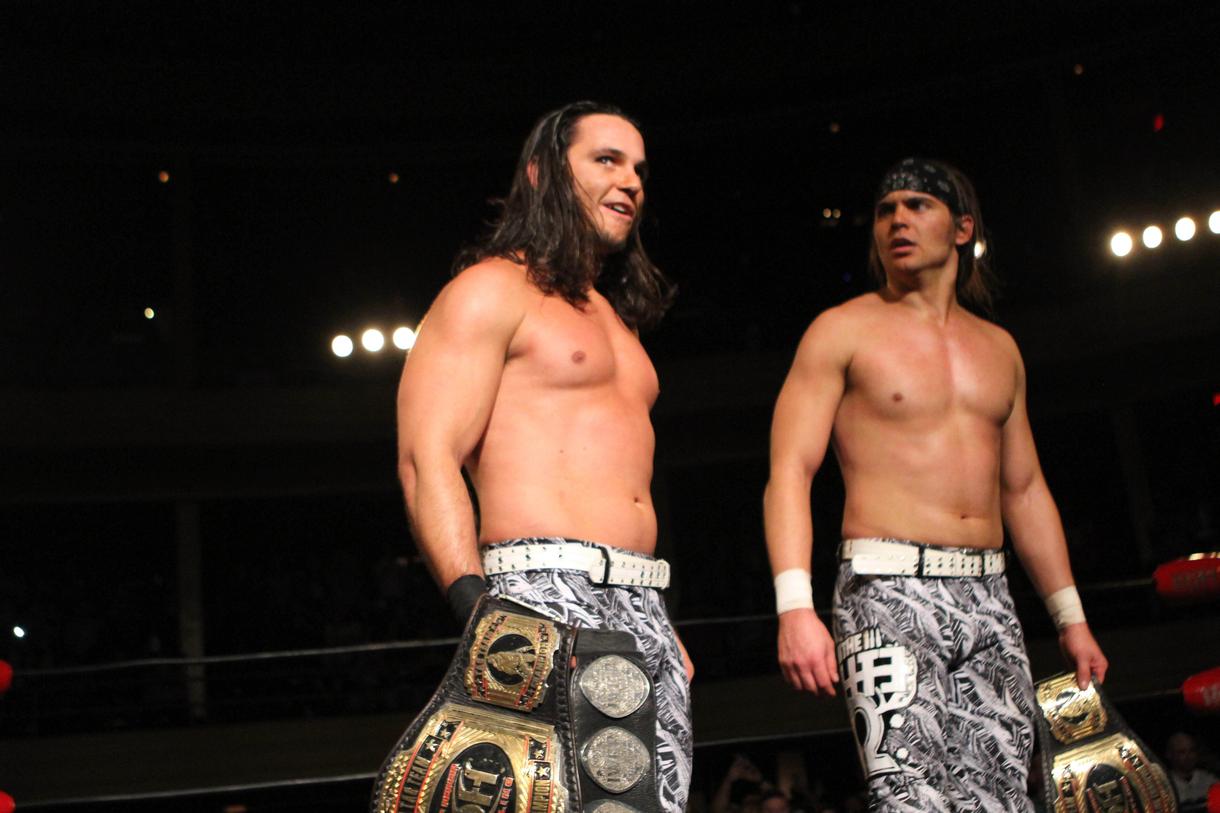

Matt Jackson, left, and his younger brother, Nick, seen here with two of the three championship belts they currently hold. Courtesy Ring of Honor Wrestling

The Young Bucks want you to hate them. Were it not for two things, you probably would, too.

It starts with their look: flamboyant spandex pants, liberal amounts of fringe, shoulder-length hair pulled into ponytails, and, in Matt’s case, a pair of muttonchops so robust they would make Elvis blush. Their faces border on pubescent. It’s the classic good-guy archetype from thirty years ago, which, in a medium where anti-heroes reign supreme, makes them exactly the sort of wrestlers you’d want to punch in the nose.

And the Bucks do their damnedest to goad the sentiment along: after getting heckled for looking like the Hanson brothers, they changed their entrance music to “MMMBop.”

They borrow bad-guy tropes from the 1990s wrestling they grew up with, and distend them to the point of total ridiculousness. The New World Order, the heel stable led by their childhood hero, Hulk Hogan, coolly saluted one another with the “Too Sweet” hand sign, so Matt uses the gesture to poke opponents in the eyes. D-Generation X, led by their other childhood hero, Shawn Michaels, crotch chopped and told opponents to “suck it,” so Nick lies in the middle of the ring, thrusting his pelvis at anyone within firing range, and Matt crotch chops the entire length of the ring to clothesline people.

Then there is the superkick, a sideways kick to the opponent’s jaw. Once upon a time, it was Michaels’ finishing maneuver, and among the more sacrosanct moves in wrestling. It’s far more commonplace today, and the Bucks spam it as much as possible. Nick estimates they’ve thrown roughly 50,000 of them in the past decade and the list of unfortunate recipients includes but is not limited to: Japanese fans, ring announcers, TV commentators, cameramen, Elmo, their own father, a former Playboy playmate, a female wrestler (while using a high-top coated with thumbtacks), and, oh yes, nine-year-old Luke.

Fans should despise this. Fans should despise them. Instead, they’re beloved, even by the people who shout “Fuck the Young Bucks” while they wrestle.

Some of this has to do with how wrestling has changed. Storylines and promotions used to dictate from above which wrestlers were the good guys and which were the bad—and therefore who you were supposed to cheer for. Today, fans are less likely to listen. They boo John Cena, the greatest ambassador wrestling has ever known, because he won’t change up his routine. They rally behind WWE’s current bad guy champion, Kevin Owens, because who doesn’t appreciate a husky guy who can fly through the air, dazzle on the microphone, and is a devoted family man to boot?

In the case of the Young Bucks, fans cheer because they’re the best tag team in the world by virtually every measure.

On December 3, 2016, the Young Bucks signed a two-year contract extension with Ring of Honor Wrestling and New Japan Pro Wrestling that made them very rich, and surprised most of the wrestling world, which for months had assumed they would be courted by WWE. The deal also allows them to work at Pro Wrestling Guerrilla, their home promotion in Reseda, California, and the hottest local show in the country. Between the guaranteed money in the deal, their per-appearance rates at New Japan, and their mountainous merchandise profits, the brothers will earn similar money to a midcard act on WWE’s Monday Night Raw to work for three companies that, combined, attract a sixth of WWE’s total live audience.

For someone to spurn possible interest from a big promotion like WWE and stay independent would be unfathomable at almost any other time in professional wrestling history, but the Bucks are different.

“It’s very important for us to show the guys there’s hope,” Matt says. “You don’t have to go there.”

They have considerable control over their characters, something they would not have had they signed with WWE. And now, in an industry dominated by a single monolithic corporation, they’re as famous as independent wrestlers can be.

“They’ve reached a ceiling and actually created a higher ceiling of what can be done without somebody in charge going, ‘I’m making you two stars, I like you,'” says Dave Meltzer, who has covered the sport since 1971 and has been called the Roger Ebert of wrestling journalists. “They’re as big a star as you’re going to get without being on national television.”

Only five years ago, however, the Young Bucks weren’t concerned about going viral. They were simply trying to stay afloat.

Pro wrestling’s history in the United States is marked by a workforce struggling to adapt in the face of gradual monopolization. The sport’s first golden age, during the 1940s and 1950s, was defined by its territories, small fiefdoms organized by strict geographic lines. The arrangement held until 1983, when the New York–based WWE (still known as the World Wrestling Federation, before a lawsuit in 2002 forced the name change) began to gobble up other promotions in an attempt to go national. An arms race ensued, and by the 90s the list of viable places for talent to make a decent living was down to WWE, World Championship Wrestling (WCW), and, on a smaller scale, Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW). The latter two went bust in 2001 and WWE quickly purchased their assets, cementing its position as a global monolith. With the (sporadic) exception of the financially shaky Total Nonstop Action Wrestling (TNA), WWE hasn’t experienced anything close to a true competitor since.

As the bigger promotions shriveled up, independent wrestlers had two options. A handful worked in other countries, primarily Japan or Mexico, but the majority tried their luck on the independent circuit, booking individual dates at bingo halls or high-school gyms across the country for as little as $50 a show. Bigger paydays, then only in the hundreds of dollars, were almost exclusively reserved for talent who previously had worked major promotions.

“When I started wrestling, there was no such thing as an independent wrestling superstar,” says Colt Cabana, an indie-scene veteran who debuted in 1999.

WWE handles all merchandise sales in-house, with talent receiving a portion of the profits. Independent wrestlers, meanwhile, are permitted to sell their own at every show. In the early 2000s, Cabana remembers, the average pre-show marketplace amounted to everyone huddling around a single fold-up table to sling signed 8 x 10 photographs or, at most, a video cassette of their matches.

Cabana, who had earned a business degree at Western Michigan, was one of the first indie wrestlers to think a little bigger. He began to print his own T-shirts, and sold merchandise online to fans all over the country. Other wrestlers began to catch on, and Cabana found himself at the forefront of a generation that didn’t need television to get noticed. Independent wrestling was slowly becoming a viable business—the foundation on which, years later, the Young Bucks could construct a mega-brand.

None of that stopped Cabana from jumping to WWE when he was offered a developmental deal in 2007—even though that meant halving his income, forfeiting his merchandise business, and putting his body through a far more punishing schedule.

“I was investing in my future,” Cabana remembers thinking.

But he was released in 2009. He returned to the indies, and watched the strategies he helped pioneer evolve into standard practice. Now there are more promotions than there have been in years—and, with the rise of YouTube and internet pay-per-view, more ways than ever to watch wrestling. But life as an indie wrestler is still a hustle, Cabana says. You need to build a brand strong enough to withstand not being on basic cable week in and week out.

What no one anticipated was the possibility that an act could balloon so big under those conditions that they would not only make a great living on the indies but reach the point where they didn’t need, or even want WWE.

But it happened. All it took were two brothers willing to break nearly every rule about how pro wrestling works.

Matt Jackson is more bombastic of the two brothers. Courtesy Ring of Honor Wrestling

Matthew and Nicholas Massie were born in Rancho Cucamonga, California, the middle two of four children. For as long as anyone could remember, Matt was obsessed with professional wrestling: the pageantry, the outfits, the seismic personalities.

“Every birthday, it was written out: WrestleMania,” their mother, Joyce, says. “Every year. He’d invite all his friends over, have a pizza party, and they’d watch that.”

It wasn’t long before Nick and Malachi, the youngest Massie sibling, joined in. By the time Matt was a teenager, their father, Matthew, a minister on the weekends and a general contractor by trade, made his sons a deal: Work on my crew during the summers and, together with the money you earn, I’ll help you build a ring.

The Massie men toiled for months, making supply runs to the hardware store and hammering down the wood frame and setting the ring posts into concrete. The backyard ring was completed on Matt’s 16th birthday.

Two and a half years later, in 2003, the family moved 40 miles north to Hesperia. Matthew’s construction business was booming, so rather than rebuild the old ring, they splurged on a portable model. With it came a new, far more ambitious idea: they would start a promotion, High Risk Wrestling.

While their parents assisted with the legwork, it was 19-year-old Matt who handled the bulk of the day-to-day business. Every Thursday, they would rent out a local skating rink for shows, and sometimes coaxed legitimate names into appearing on the card: their future Ring of Honor promotion-mates Christopher Daniels and Frankie Kazarian, one-time WCW star Chris Kanyon, and even Marty Jannetty, Shawn Michaels’ old partner in a tag team called the Rockers. “I’m struggling to get through college at their age and they’re running a promotion,” Daniels marvels years later.

The brothers booked themselves, too, and cultivated a reputation in Southern California as solid workers. In early 2005, they were booked on a card at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles, in what was then the biggest show of their lives. When they showed up, they found out that they were tagging together instead of working singles the way they wanted to at the time. Even worse was the name. Their ring names at the time, Mr. Instant Replay and Slick Nick, were nowhere to be found on the bill. Instead, they were just Matt and Nick, the Young Bucks.

“We thought that was lame,” Matt says. “We came out to that one song by Twisted Sister, ‘We’re Not Gonna Take It.’ Immediately, we were like, ‘Oh, this is the worst. We’re coming out to the whitest song ever. They’re calling us the Young Bucks.'”

It wound up working better than anything they’d done on their own. The company immediately asked them back for another show and, soon, more doors began to open. The brothers were hardly enthused, but they were pragmatic. People wanted to see the Young Bucks. The name stuck, and so did the tag team. Another promoter decided that they needed a surname, and soon they were the Jacksons. “Immediately, the first thing we thought about was Michael Jackson,” Nick says. On occasion, when working with Malachi, they called themselves the Jackson Three. (Exhausted by the travel, Malachi retired from wrestling in 2010.)

Before long, Matt and Nick were working every prominent indie in the United States. In December 2009, they received their big break: a one-year contract with TNA, the country’s second-largest promotion. The brothers were rebranded as Max and Jeremy Buck, together known as Generation Me, and thrust onto national television in a program with the company’s hottest tag team, the Motor City Machine Guns.

The feud would burn long enough to earn a new two-year deal, but things began to go south almost as soon they signed it. The brothers were split up, pitted in singles matches, and eventually in a short-lived feud with each other, an idea they were vehemently against but reluctantly went along with. They were thrown back together soon afterward, but their momentum, and the TNA creative department’s plans, had stagnated. The contract paid by the appearance and when the company ran out of ideas for them, the brothers sat around for weeks waiting for a paycheck. They were trapped—miserable when they were working and being bled dry financially when they weren’t. Finally, in July 2011, Matt and Nick terminated their contracts with TNA.

To this day, Matt remembers the trip home to California after he and Nick quit the company. Matt’s wife, Dana, was six months pregnant at the time, and they were on the verge of getting kicked out of their apartment. It was their rock bottom as pro wrestlers, but it was also the point at which they realized they needed to find another way if they were going to make it.

Matt recalled a specific layover when, famished, he ducked into an airport Popeye’s to pick up lunch, only to have his credit card declined. He needed Nick to pick up the tab on his $1.99 chicken biscuit sandwich.

“I almost broke down in the airport,” Matt says. “That was almost a moment for me: I’ve got to do something. I’ve either got to get a job or make this wrestling thing work. I always have that fear in my head. I can’t go back to those days of being a poor, starving artist. I want to succeed. That’s what drove me to be the guy I am now. That moment.”

For years, Matt and Nick had been consumed with becoming the very best wrestlers they could be. Do that, they figured, and the money would follow. TNA had opened their eyes. Being great wasn’t enough. If they wanted to survive, they needed to become Colt Cabana.

What is Colt doing that is so successful? Matt wondered. Why is he making so much money? How is he doing this?

Soon, Matt and Nick were printing their own shirts, too. They incorporated social media. They paid more attention to their downsides—the lowest minimum guaranteed payment they could receive for an appearance—and, when business picked up, how to diversify revenue streams.

They also changed their style. Matt and Nick had just spent two years ensnared by someone else’s rules—how to wrestle, how to perform, how to act, how to look. Now that they were on their own, they followed only one guideline: It had to be fun.

“Let’s do it our own way,” Matt recalls saying. “Let’s be ourselves. It took not having fun for two years to realize what having fun was again.”

The more they dug into where they were having fun, the more they were convinced that the answer lay back in California at Pro Wrestling Guerrilla, the promotion where they were first discovered. That was where they felt free to bark back at the audience and indulge the most ridiculous aspects of 90s wrestling nostalgia. At TNA, Max and Jeremy Buck were clichéd heels. Matt and Nick Jackson were unlike anything the business had seen.

“We really decided, ‘Hey, our most success has always been at PWG. Let’s take this PWG act and bring it everywhere,'” Matt says. “Once we started doing that, it wasn’t just the people in Reseda who wanted to see these guys, it was everybody. We realized that this act was working.”

Nick Jackson, seen here giving a fan a Too Sweet. Courtesy Ring of Honor Wrestling

What makes the Young Bucks so popular?

First, there is the wrestling itself. Matt and Nick’s work—athletic, high-flying, tandem-based offense—is regarded as the standard within their brand of tag-team wrestling. It isn’t just the degree of difficulty or the different permutations of the moves they try, though those are considerable. It’s their ability to execute all of it with a minimal error, in total symmetry, all while remaining cognizant of how the crowd will react.

The Wrestling Observer Newsletter Awards—the Oscars of pro wrestling—has voted them Tag Team of the Year in all of pro wrestling in each of the last two years. They have invented moves on two separate occasions that went on to earn Best Wrestling Maneuver.

Meltzer runs the Wrestling Observer Newsletter. He also popularized the five-star rating system now ubiquitous throughout the sport. Only four matches this year earned a perfect rating, and the Young Bucks were in one them; it was the first five-star match in North America since 2012. Of Meltzer’s top 15 matches, the Young Bucks were in three, the most of any tag team.

Then, there’s how the wrestling is performed.

The best way to explain it is to begin with one of their innovated moves: the Meltzer Driver. It’s named for exactly who you think it is, and it’s because the Young Bucks want everyone to know that they only put on five-star matches. Matt and Nick refer to Meltzer as Uncle Dave, because why wouldn’t wrestling’s Scorsese be on familiar terms with its Ebert? When Meltzer saw them wrestle in person at a show in February, the match’s climax began with both brothers turning to Meltzer in the crowd midway through the flow of action, blowing him a kiss, and then executing the Meltzer Driver in front of its inspiration.

So yes, two performers named their signature trick after a 57-year-old journalist they have met a handful of times, and whose significance to them lies only in critiquing their work, which they themselves purport is the very best thing in existence. Out of context, the act sounds, at best, like excessive self-congratulation. At worst, it’s embarrassing.

But in today’s professional wrestling, everyone is in on the joke. It’s a safe bet, in other words, that most everyone attending a Young Bucks show knows who Dave Meltzer is, just as those same people likely have a working knowledge of his five-star rating system. So there was only ever going to be one outcome once the Young Bucks gave some PDA to their muse: the building went apeshit.

Matt and Nick anticipated this, of course. They are the tag team of the internet generation, practitioners of self-aware, postmodern wrestling. “Our act is pretty much your routine tag team wrestling, but you’re on cocaine,” Matt says.

The act is designed to operate on multiple levels. If you want nostalgia—the crotch chops, the “suck it,” the gratuitous imitations of wrestlers living and dead—well, the Young Bucks can do that. Or you can watch them as a circus act: bright costumes, brilliant acrobatics, plenty of playing off the crowd. But the reason why the Young Bucks transfix the hardcore fans as much as the casual ones lies in stunts like the one with Meltzer, and what they represent: bringing the wrestling nerd subculture into the mainstream.

Their act actively rewards the obsessive who follows them on Twitter and reads up on the latest gossip, and binges wrestling podcasts, and watches every match she can get her hands on. The more dedicated the fan, the more rewarding the performance will be. There is no learning curve like that anywhere else in wrestling.

Perhaps their greatest bit of misdirection is that for as cutting-edge as they are, the Young Bucks are actually the last of a dying breed: the old-school tag team. Over the past two decades, virtually every team of consequence has split up to work singles, either temporarily or permanently. It’s a template laid out by WWE, which pays its singles stars far more and rarely features tag teams as a show’s main event.

Consequently, wrestlers often focus on establishing their individuality within the tag team, in preparation for when they eventually split off. Meltzer calls it “the Shawn Michaels progression,” after the Bucks’ hero who achieved superstardom only after he ditched Jannetty to go solo.

“I’d rather quit the business than work singles,” Matt scoffs.

The Young Bucks first became famous for their athletic, tandem-based maneuvers. Courtesy Ring of Honor Wrestling

It’s April Fool’s Day, and the Bucks are milling about in the lobby of Hyatt Regency in downtown Dallas. It’s time to make money. Two days from now, on Sunday, April 3, WWE will cram north of 70,000 people into AT&T Stadium for WrestleMania, its biggest show of the year. Every year, too, independent companies from all over the country converge on the host city the weekend leading up to the show, and put on events of their own. It’s the underground scene’s chance to show up the mainstream.

Later that night, Matt and Nick will headline the first of Ring of Honor’s two shows that weekend, wrestling the Motor City Machine Guns for the first time since TNA. Several hours beforehand, they’re setting up for a paid autograph session. For $30, fans can get one item signed and pose for one photo with the Young Bucks.

A ROH official gives the Bucks a rundown of the rest of the lineup. Among them: Daniels and Kazarian; reDRagon, another of the world’s top teams; Quinn Ojinnaka, a colossal former NFL offensive lineman who wrestles under the name Moose; and Jay Lethal, who at the time was Ring of Honor’s World Champion. Each is one of the company’s trademark acts, with an established fan base and a reputation for doing good work in the ring.

“Well, good luck to them,” Nick chuckles.

What happens next is what always happens when the Young Bucks are on a show. It doesn’t take long for the crowd to divide itself into two lines: one for the Bucks’ table, which is farthest from the entrance, and one for everyone else. Midway through the availability, the Bucks’ line stretches 60 people long. Jay Lethal has a little over half that. The remaining eight wrestlers patiently wait for stragglers, fiddling on their cell phones, chatting amongst themselves.

Meanwhile, the Young Bucks are on their feet, holding court. Everyone gets a warm greeting, with Matt frequently beckoning guests to give him some sugar—to Too Sweet him. They quiz everyone on their plans for the weekend, and which shows they’re attending. They brought their title belts with them, too, and eagerly foist them upon fans to take a picture. “Here, you be the tag champs,” Nick tells a pair of fans. At least a half-dozen ask for their photo to be a pantomime of getting superkicked and the Bucks gladly oblige, grabbing on to the table for support and positioning their heels as close as possible to each fan’s chin. The availability is supposed to last for two hours, but Matt and Nick are still signing 30 minutes after everyone else has gone. They finally close up shop with only 15 minutes to go before the Ring of Honor show gets underway.

Matt’s back is sore after being on his feet for all those hours. Already, at 31, he has trouble bending over to get his laundry out of the dryer; he can’t sit on the floor too long to play with his daughter. He and Nick understand, however, that for the fans these events are far less about buying a product than they are about interacting with their idols. They want to make it worthwhile, and so he stands. “That’s why they’re here,” he says. “You have to be welcoming.”

“They have this aura about them that makes people want to like them and wear their shirts, represent them,” says Joey Ryan, a close friend of the brothers and a 16-year veteran of independent wrestling. “They can be cool and they can be unique and they can be fun. Even as bad guys, they’re endearing.”

They also know how to market. Their liberal use of superkicks spawned 25 different shirts featuring the word, usually in concert with the Bucks’ biggest branding effort, Superkick Party, which is at once a term for kicking someone in the head a bunch of times and event-based marketing.

“Everyone seemed to poke fun at us and say, ‘The Young Bucks are the guys who do the superkicks,'” Matt said, recalling the original idea. “Yeah, you’re right, we do a lot of superkicks. You know what? It’s awesome. Let’s call it a party.”

All told, you can find more than 80 different Young Bucks shirt designs on sale at ProWrestlingTees.com, the online marketplace where they and every other wrestler not actively working for WWE hawk their wares. According to the site’s founder, Ryan Barkan, the Bucks move an unfathomable amount of merch. The site features shops for more than 1,200 wrestlers, including household names like Stone Cold Steve Austin, CM Punk, Macho Man Randy Savage, Mick Foley, and Diamond Dallas Page.

The Young Bucks are currently Barkan’s second-highest seller, behind only Austin, arguably the most popular professional wrestler ever.

“The Bucks aren’t on TV in front of millions of people every Monday, but somehow they’re selling more shirts than 99 percent of the people on the site, which is crazy to me,” he says.

That’s before their cut from the autograph signings or the merchandise they move in Ring of Honor’s official shop. Nor does it include their own store, YoungBucksMerch.com. Matt’s wife, Dana, runs it and handles the orders, which include items as wide-ranging as trading cards, tracksuits, water bottles, silicone wristbands, flags and a whole line of kid sizes. Factor in the guaranteed money from their contracts, and each brother’s income is comfortably in the six-figure range. Forget merely surviving on the indies; the Young Bucks are wealthy.

“They’re the first people that opened my eyes to seeing, ‘Oh, you can be successful outside of the WWE. You can make a full-time living in wrestling without the WWE. You can have a career in wrestling without the WWE,'” Ryan says.

What the Bucks have done that’s different is to turn the business of being an indie wrestler into part of their act. It was a natural extension of what they do inside the ring: twisting tired wrestling tropes into inside jokes. The jokes continued on social media, where they could continue to develop their characters—and sell merchandise—24/7. After WrestleMania weekend, they tweeted out, “Thank you Dallas. You gave me lots of money tonight.”

Anyone can push out merchandise links. The Young Bucks effectively make them into promos. How else could they get away with making Superkick Party the app, in which the player superkicks other wrestlers to help make the Bucks money at the merchandise table?

“The match is just an infomercial for the t-shirt,” Matt texted me in May. He then decided that statement was tweetable. I asked how many retweets he thought he’d get for it that day. “100 at least.” It ended up getting there in a few hours.

The Young Bucks have now set their sights on conquering YouTube. Earlier this year, they launched Being the Elite, a series that follows the Bucks and Kenny Omega, their friend and stablemate in Japan. It’s their take on reality TV. They check in from airports, at autograph signings, at home, wherever. It satiates fans’ constant appetite for more glimpses behind the curtain, and is their latest attempt to shatter the dwindling barriers between the performers and their audience.

It helped the product spread globally. In August, the Young Bucks wrestled the Hardys in Santiago, Chile. It was their first time working there and, as Americans working without the benefit of a huge television audience, they anticipated a tepid reception at best.

Instead, Matt says, “they’re chanting ‘Superkick’ and ‘Young Bucks’ and doing our Elite chant…. To see the people and little kids who don’t speak our language, they all speak Spanish, but they can perfectly pronounce ‘Superkick Party.’ Some of them were saying ‘Too Sweet Me.’ It’s like, wow. They know our lingo, even.”

“They’ve achieved stardom in a different way from almost anyone else, and they’ve been able to market themselves really creatively,” Meltzer says. “They made themselves stars through all these different aspects.”

The Young Bucks’ signature in-ring pose. Courtesy of Ring of Honor Wrestling

The Young Bucks aren’t quite as independent as they used to be. Until late last year, when they signed their first Ring of Honor–New Japan deal, they were barnstorming the country without a safety net, working as many as five shows in four days. Demand was booming to such a degree that one promotion—2CW in Oswego, New York—named its July 19, 2015, event “We Booked This Show Because It Was Literally The Only Available Date For The Young Bucks.”

But the nonstop travel wore them down. Matt suffered an avulsion fracture in his right ankle working a show in Illinois; fearful of missing dates, he taped it up and kept wrestling. The Bucks put out word that they’d be willing to sign an exclusive contract, sacrificing freedom in exchange for fewer dates on the road and more overall peace of mind. Their eventual agreement with Ring of Honor and New Japan—one that ROH president Greg Gilleland says was, at the time, “the highest [financial] length we’ve ever gone” to sign a wrestler—came after months of speculation over which of the world’s most prestigious companies were bidding on the Bucks, and how many of them had made offers.

About two years ago, Matt and Nick concocted a ten-year plan: spend a decade working their high-octane and making as much money as possible. “And if we can get out, that’d be great,” Matt says.

So where does WWE figure in their plan? It isn’t that they want to go there, per se. Pragmatically speaking, they understand that they probably shouldn’t. Their Ring of Honor deal covers hotels and rental cars, expenses that WWE talent handle on their own. They work fewer dates, too, which means smaller road expenses and paying taxes in fewer states and, most importantly, more time at home.

“Maybe that’s our claim to fame, that we’re the only guys that didn’t go when everyone else did,” Matt says.

But the brothers don’t eliminate the possibility of joining WWE, either. “If we ever wanted to become wealthy—like, wealthy wealthy—we need to go there,” Matt admits. “We’ll never, ever have the potential to make a million dollars on the indies, that’s for sure. That’s just not going to happen.”

Which isn’t to say it necessarily will in the WWE. Even there, only a handful of wrestlerscrack the seven-figure mark, and befitting WWE custom, all are singles stars. Would the company really defy its own history and fork over two million dollars a year for the brothers to share?

There’s another, more personal reason for going WWE, though: there’s nothing left to prove on the indies. The Bucks have wrestled every opponent, done every match, held titles everywhere they’ve worked. They’re playing the long game now: whether it’s in ten years or 25, they want to retire as the greatest tag team of all time. And the only stage left is the one that matters most to the people judging their legacy.

“You have to go there to be the greatest of all time,” Matt says. “That’s in the eyes of the fans. Unless you’re a WWE Hall of Famer eventually, you almost have a wasted career in their eyes. It’s sad that it’s like that.”

By the time they are free agents again, Matt will be 33 and Nick, 29. “Maybe then we think, You know what, if we’re ever going to go to [WWE], let’s go now. Because it’s going to be now or never.”

This will-they-won’t-they routine between WWE and the Young Bucks has been going on for more than five years. Soon after getting released by TNA, the brothers were invited to a tryout, and the parties have flirted on and off ever since. The Bucks would periodically stoke the flames on social media, and WWE would occasionally check in to keep tabs. They turned down an opportunity to audition again in 2014, but say there were informal discussions in the months leading up to their first ROH deal—although, Matt says, “We’ve never really had a real offer on the table.”

Last year, they may have come closer to joining the company than anyone realizes. The door nearly creaked open by way of A.J. Styles, their one-time stable-mate in New Japan and the current world champion of WWE’s SmackDown brand. In January 2016, Styles and two other Bullet Club members, Karl “Machine Gun” Anderson and Doc Gallows, left New Japan as part of a WWE talent raid. The Massie brothers say that, had the move come a few weeks earlier, they may have joined in.

“When A.J. was about to leave, he pulled us aside before anybody knew anything and he asked us about our contracts,” Matt recalls. “At that point, it was December and we had just signed—we signed in November. He’s like, ‘You did? Ughhh.’ The idea was he was going to try and get us to walk out with him and be the guys with him… If we never signed, there’s a great chance we could have been walking out on Raw with those guys, I feel.”

Regardless of where it leads, the Young Bucks are already preparing for the end of the road. They’ve opened a separate account to set aside all of their merchandise money for savings. In ring, they’re slowly transitioning into character-driven wrestlers, paring back their more dangerous stunts. “Certain dives to the floor, I’ll say, ‘Yep, that’s a once-a-year,'” Nick says. For all the money the Superkick Party brings in, its greatest value lies in how the Young Bucks’ brand can preserve their bodies. Matt and Nick Jackson throw superkicks now so Matt and Nick Massie have a better chance of making money long after most high-flyers break down

The next evolution is always on the horizon. Matt recently texted Nick that he was contemplating cutting out “Suck It”s altogether, a move on par with Depeche Mode phasing “Personal Jesus” out of their live shows. “He’s always saying we’ve peaked,” Nick laughs. “And I’ll say, ‘C’mon, we’ve got to enjoy the ride.”

It’s a party, after all. Everyone’s invited.

[Source:-Vice Sports]