WASHINGTON — Over the past week, as Senate Republicans feverishly cobbled together their doomed health care bill, Chuck Schumer, the Democratic leader, made several quiet visits to the private “hideaway” office of John McCain, Republican of Arizona, near the Senate chamber on the Capitol’s first floor. Senator McCain, who recently received a brain cancer diagnosis, was nervous about the bill, which he thought would harm people in his state, and elegiac about members of his storied family, reminiscing about them at some length.

During those visits and in several phone calls, Mr. Schumer, who had led Democrats in a moment of prayer for Mr. McCain, assured him that they would have the 80-year-old senator’s back in his quest for bipartisan legislation should the health repeal fail — including making sure Mr. McCain’s beloved defense bill was passed.

“To me it was poignant,” said Mr. Schumer, who choked up on the Senate floor early Friday when talking about Mr. McCain. It was Mr. McCain who cast the decisive vote that led to the health care bill’s demise.

“It reminded me of going to Ted Kennedy’s hideaway and talking to him when he was ill, when he would show me pictures on his wall,” Mr. Schumer said. “I had a lump in my throat several times.’’

Those assurances, whether they pushed Mr. McCain to vote against the bill or not, say a great deal about Mr. Schumer, who has held the Democrats together even as he has promised to work with Republicans. Six months in as leader, Mr. Schumer has melded the blustery negotiating strategies of his predecessor, Harry Reid of Nevada, with the cagey tactics of Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the majority leader, who honed the art of obstruction as a weapon.

Continue reading the main story

Continue reading the main story

Now that Democrats have defeated a major plank of the Republican agenda, the question is whether that success will drive President Trump and the Republican leadership to the negotiating table — and whether Mr. Schumer can keep Democrats who are up for election in red states in line and safe from defeat next year.

While Republicans have spent the last six months enmeshed in internal squabbling, Mr. Schumer has largely made sure Democrats stood on the sidelines. Mr. McConnell cut out Democrats on Day 1 of this Congress, using every method to bypass them on deregulation votes, cabinet confirmations, a tax overhaul and health care policy.

“That has had a big impact,” said Senator Dianne Feinstein, Democrat of California. “If you leave out a whole political party,” she said, “and then you chasten them for not helping, well, that unites that party.”

Yet Democrats give Mr. Schumer — song-belting, frequently badgering, endlessly frenzied, publicity hounding — credit for his tireless attention to senators from every faction, and for quiet outreach to Republicans who he thinks could be partners down the line.

He has worked carefully — far more than Mr. Reid, many Democrats agreed — to be almost relentlessly inclusive, talking with them at all hours of the day, over every manner of Chinese noodle, on even tiny subjects, to make them feel included in strategy. Recently, as he sat in a dentist’s chair waiting for a root canal, he dialed up Senator Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut to talk about a coming judiciary hearing concerning Donald Trump Jr.

“I think he makes it look easier than it is,” Mr. Blumenthal said about Mr. Schumer.

Mr. Trump’s election stunned him.

Mr. Schumer’s original plan after the election was to find a way to work with his fellow New Yorker on issues where he thought they might align, such as an infrastructure bill.

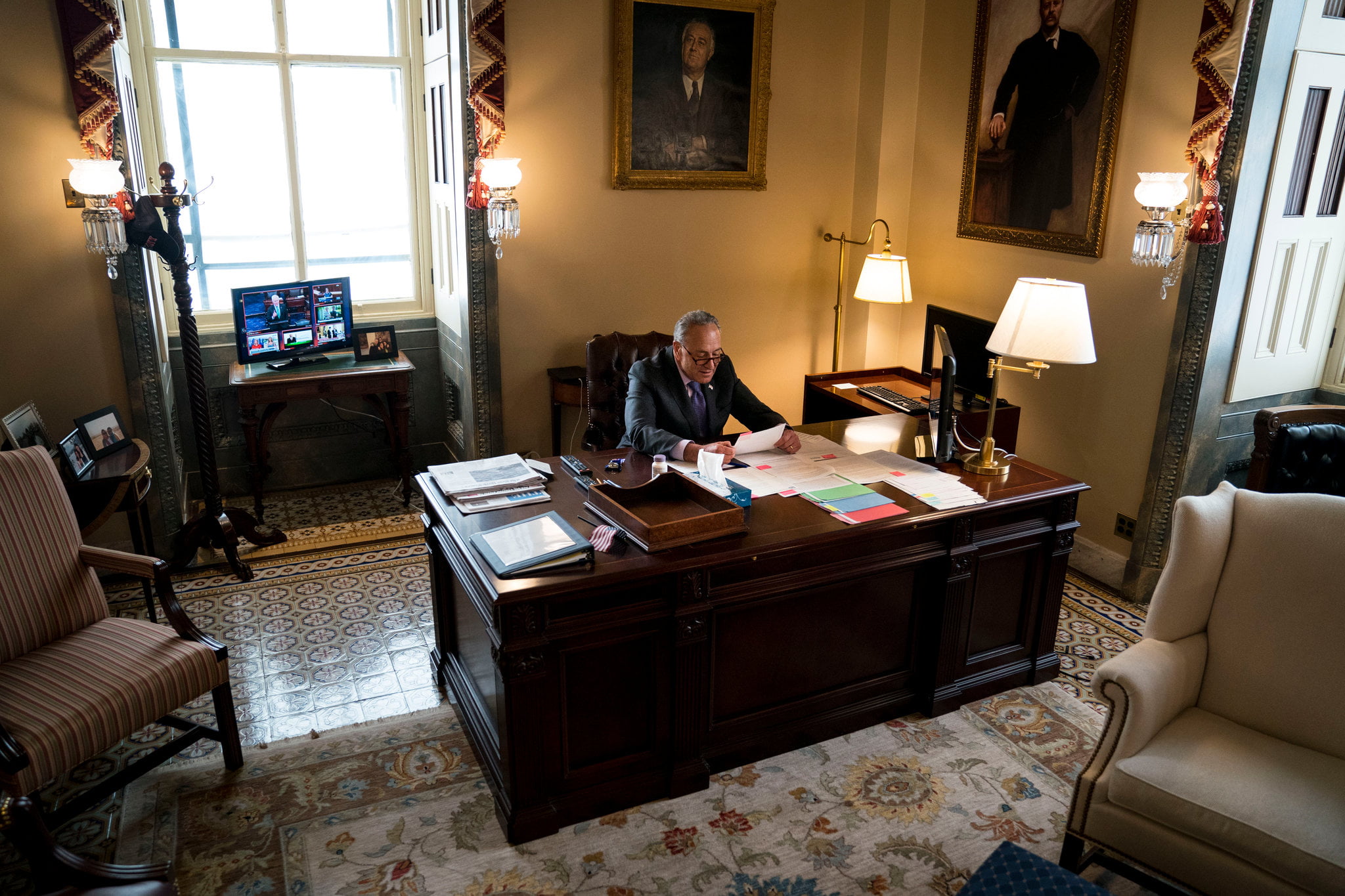

“I take what’s given me,” Mr. Schumer, 66, said in a (shoeless) interview in his Capitol Hill office right off the Senate floor, one festooned with portraits of his idols (Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt, Lyndon B. Johnson), maps of New York and mildly goofy photos with other Democrats.

Fleeting dreams of using Mr. Trump’s populism to triangulate against a Republican-controlled Congress dissolved, he said, when Mr. Trump instead decided to move right away to repealing the Affordable Care Act. So Mr. Schumer turned to an opposition agenda, doing everything within his limited powers to slow, block or obviate Mr. Trump’s agenda.