“How will social media be used in future elections?”

This is the question that always seems to follow any conversation I have about social media’s impact on the 2016 election. Observers within the US and abroad watched Donald Trump turn his personal Twitter channel into a driver of earned media and voter engagement in ways that defied conventional election wisdom. Using social media as his strategic foundation, Trump was able to mount a successful campaign for the GOP nomination and a general election campaign that was able to toe-to-toe with the well-heeled and expansively organized Hillary Clinton campaign (at the time of writing, the outcome of the election is yet to be determined).

Naturally, people are wondering if Donald Trump represents the future of political campaigns or if he is an aberration.

Meanwhile Hillary Clinton’s campaign employed the next generation of two successful Obama campaigns. Her campaign integrated social media, big data, traditional advertising and an extensive offline field operation into a coherent whole. But while social media played a very important role in her campaign, Clinton never embraced social media at the personal level we saw Trump employ. Nevertheless, her campaign was able to go toe-to-toe with Trump’s campaign, despite an email scandal that dogged her to the very end, including an eleventh-hour bombshell dropped by the FBI.

Given this backdrop, there are three ways social media are likely to be employed in future elections.

Note that I said “social media are,” not “social media is.” Aside from the fact that “media” is plural and grammar dictates “are” and not “is,” social media is not a monolithic thing. When analyzing social media, we must differentiate between social media channels and between distinct audiences within each channel. That said, here are three ways that social media will be used in future elections:

1. Using social media content to better predict voter behavior

2016 saw the rise of nightly voter persuasion modeling to guide the targeting of the next day’s voter outreach (door knocking, phone calls and email). These models depended on tracking polls, developments in the news and a variety of demographic and geo-context data. And while there was some attention paid to the social media activity on the candidates’ own Facebook and Twitter channels, they generally didn’t use content analysis of the vast number of social media posts by voters on their own channels.

Despite the obvious concern for the amount “noise” about candidates across social media and the challenge of machine-coding sentiment, content shared on social media about the candidates can be very illuminating to campaigns. Knowing how people feel about the candidates (sentiment) and what issues they connect to each candidate is invaluable information. Incorporating these into voter persuasion models will not only help with traditional voter outreach, but it’ll enhance social media-driven voter outreach.

The trick is to segment social media listening and content analysis by geo-location. Up to now, geolocating people on social media has been problematic because:

1) Very few people directly disclose their location

2) Methods for inferring location are still imprecise (though improving).

But there are new ways being developed to geolocate voters on social media that will dramatically improve our ability to do this in future elections.

2. More personal use of social media by candidates (but not quite like Donald Trump)

Donald Trump showed us both the power and the pitfalls of candidates driving their own social media channels. Trump was able to use his Twitter account to create a personal connection with his supporters, creating a greater sense of political efficacy among them – tied to himself. Because he was the author of his own tweets (dictated to an aide during the day and typed by himself after 7:00 pm), and because he would interact with voters, reporters, and other candidates he created a sense of accessibility never seen before in a presidential candidate.

Further, because Trump was gifted in his ability to create powerful simple messages, he was able to undermine his opponents’ efforts to talk about complicated issues. This was especially enhanced by his large audience of rabid retweeters.

But Trump has also been undisciplined with his tweeting. Oftentimes his engagement with others – including the occasional voter – was angry and retaliatory. He would too often start Twitter wars in the wee hours of the morning – and while sometimes these barrages allowed him to take command of the narrative from the previous day’s events, he didn’t always do so in a constructive manner. As a result, in the final two days of the election, his staff took his Twitter access away. This reduced his risk of his tweeting a gaffe in the final hours of the campaign, but it opened Trump up to yet another temperament attack (this time from President Obama regarding his trustworthiness with the nuclear codes).

In future campaigns, we’ll see candidates work to leverage the power that Trump was able to tap, but in a more measured way. The trick will be for candidates to create a compelling social media presence – provocative but not off-message.

3. Distributed social media channels

One of the reasons that social media content analysis is so crucial to political campaigns is that, based on review of Facebook buzz data throughout the 2016 campaign season, more than 95% of the buzz about a candidate is not driven by posts they make on their primary campaign page. People across social media are sharing articles about the candidates and sharing each other’s original comments. Given this, one way that campaigns can be the driver a larger share of the overall buzz is to create a more distributed social media presence.

The Clinton campaign, for example, maintains several social media channels on Twitter and Facebook (as well as other social networks). In addition to its primary campaign Facebook page, for example, the campaign has official pages for Chelsea Clinton, Tim Kaine, several key state pages, and The Briefing. These help to drive additional buzz for her campaign across social media. To help connect them all, the main Facebook page “Likes” the other pages.

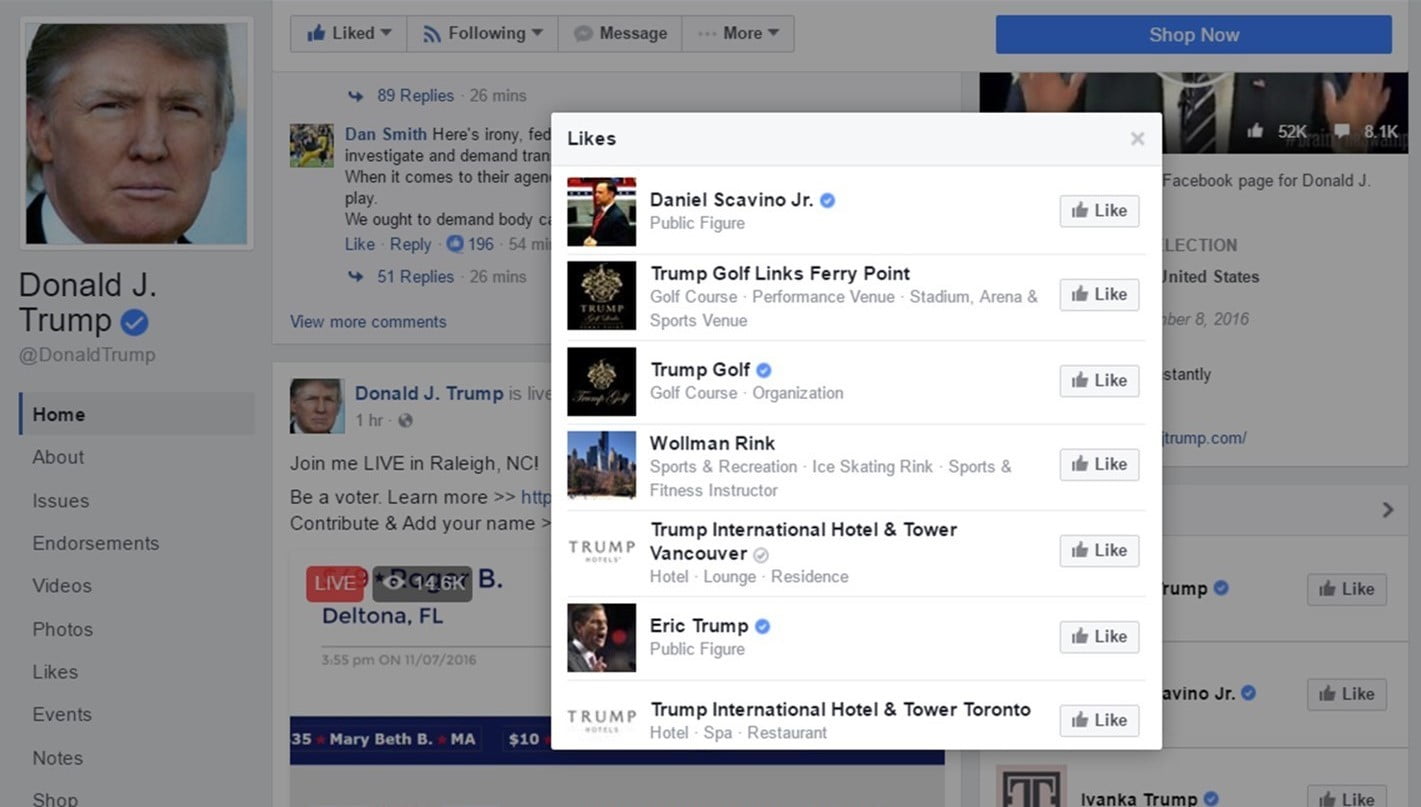

Meanwhile, the Trump campaign has a limited set of additional social media channels, all dedicated to key people within the campaign (instead of key states and constituencies), including his wife Melania, three of his five children (Ivanka, Eric and Donald Jr.) and his Communications Director Dan Scavino Jr. Interestingly, Trump’s page does not “Like” his running mate Mike Pence’s page. And unlike, Clinton’s campaign page (which only likes campaign related or relevant pages), Trump’s primary campaign page links to several pages for Trump’s personal business ventures (golf courses and hotels).

In the future we’ll likely see more of what we see in the Clinton campaign: a large interconnected network of official campaign related pages, especially ones dedicated to key states and constituencies. And we’ll see less of what Trump’s campaign offers: a limited number of campaign staff pages. Also, we’re extremely unlikely to see a candidate use his or her campaign Facebook Page to promote the candidate’s for-profit business ventures.

In general, the future of social media in electoral campaigns will be a hybrid of the two current presidential campaigns: more personal use of social media by the candidate than Clinton, more disciplined personal use than Trump, more strategic use of social media across and within platforms along the lines of the Clinton campaign, and no use of campaign channels for personal enrichment.

In other words, despite the explosive use of social media by Donald Trump, we’ll see an incorporation of what he did best on a personal level into an expansion of the professional presentation we got from the Clinton campaign.

[Source:-Social media Today]