When there’s not much to talk about – say, in the two weeks between the NFL’s conference championships and the Super Bowl – the sports chattering class loves to talk about sports towns and their varying quality. The notion itself is a false concept – there’s nothing tying the fortunes of a set of independently owned teams in a particular city together except geography, and in any city, some teams are more beloved than others and most fan fidelity depends on wins. Still, that hasn’t stopped writers at outlets like ESPN, the Boston Globe and CBS from railing against Atlanta and its fans whenever the opportunity presents itself. Here’s the thing, though: they’re wrong and always have been, and they’ve never been more wrong than they are at this exact moment, as the Atlanta Falcons prepare to take on the New England Patriots in Super Bowl LI.

When there’s not much to talk about – say, in the two weeks between the NFL’s conference championships and the Super Bowl – the sports chattering class loves to talk about sports towns and their varying quality. The notion itself is a false concept – there’s nothing tying the fortunes of a set of independently owned teams in a particular city together except geography, and in any city, some teams are more beloved than others and most fan fidelity depends on wins. Still, that hasn’t stopped writers at outlets like ESPN, the Boston Globe and CBS from railing against Atlanta and its fans whenever the opportunity presents itself. Here’s the thing, though: they’re wrong and always have been, and they’ve never been more wrong than they are at this exact moment, as the Atlanta Falcons prepare to take on the New England Patriots in Super Bowl LI.

First, let’s dispense with the idea that the numbers bear out Atlanta as a particularly bad sports town, let alone the worst in America. In the 2016 season, the Falcons were in the middle of the pack, attendance-wise, for the NFL: 14 out of 32, with an average of 69,999 attendees at home games and a 98.2 percent home stadium fill rate, according to ESPN. The Patriots, who have been the supposed crown jewel franchise of the NFL since 2001 and who are the pride of what is generally considered a “good” sports town (and maybe even the best, depending on who you ask), ranked four spots behind the Falcons and underperformed them in both the average number of home fans and home stadium fill percentage (66,892 and 97.2 percent, respectively). New England fans entered the season a decade and a half deep in a dynasty, while Falcons loyalists had little reason to hope for much beyond the uneven performances of recent years. And still, Atlanta’s supposedly terrible fans showed up in droves.

Atlanta’s attendance stats are more impressive when you consider that the NFL isn’t even the most popular football league in the state. People who believe Atlanta is a bad sports town somehow manage to convince themselves that college football doesn’t count, which is the sort of off-hand dismissal most often made by people who are well aware their point of view can’t gel without it. Matt Berry, a 29-year-old Atlanta native and lifelong Atlanta sports fan, is not willing to grant that premise. “You absolutely cannot bring up sports in Atlanta without acknowledging that this city cares more about college football than any other major American city cares about any other sport. On any given weekend, there are literally hundreds of thousands of people heading out to Athens, Auburn, Knoxville, Tuscaloosa and Clemson – all less than 3 hours from Atlanta – and yet the Dome still gets packed every Sunday. If we’re going to talk about attendance, do I not get to point to Boston College or Rutgers games?”

That’s exactly where the myopia starts to set in for fans and commentators in the Northeastern and Rust Belt cities most often associated with intense pro sports fandom – Atlanta isn’t a bad sports town, it’s just a different sports town, with different priorities and a vastly different history. Professional sports franchises didn’t even bother trying to win over Atlanta’s fans until the 1960s, which means teams across all the major leagues and the country’s regions, like the Chicago Cubs (founded in 1870), New York Knicks (1946) and San Francisco 49ers (also 1946), had anywhere from several decades to a literal century’s head start over their Atlanta counterparts when it comes to folding themselves into family and civic traditions for its fans. When the Falcons were founded in 1965, they arrived to a city with no other major league sports teams – the Braves didn’t show up until 1966, the Hawks until 1968.

By the mid-1960s, millions of people in Atlanta and across the Southeast already held rooting interests in college teams, which were far more geographically accessible to them than pro franchises in an era when the only way to keep up with most games in real time was to go see them in person or listen on local radio. Older fans who grew up in the Northeast or Midwest have memories of listening to NFL or MLB games with their dads or grandpas, which are the communal experiences that weave committed, emotional fanbases and pass down rooting traditions to each new generations of fans. The teams themselves and the people with whom you share them start to fade together. For southerners, almost all those memories and the emotional commitment they create goes back to college football. But Atlanta has caught up to the traditional powers in the type of football preferred by the rest of America, if attendance statistics are any indication.

Still, the negative stereotypes – that they don’t care, don’t bother showing up to games and don’t get loud when they do, they’re why the NHL team stuck around for about a decade before going to frozen Winnipeg – about Atlanta’s fans stick around, at least among people who have never spent much time in the city. Not only do Atlanta fans see it a little differently, but so do its athletes. When I brought the topic up to Dominique Wilkins, an Atlanta sports icon, legendary Atlanta Hawk, Georgia Bulldog and current Vice President of Basketball for the Hawks, he was ready to speak on it even before I entirely finished my question. “Atlanta is a great sports town. Back when I was playing, the Omni – that place was rocking. I had major support from fans in this town. It’s always been a sports town. The fans have been there, and they’re starving for a winner.” That Atlanta has only one championship among its professional team – the 1995 Braves World Series – should make resilience of its sports fans the envy of the athletic world. We’re traumatized, but we’re still showing up, against all odds and, perhaps, our own better judgment.

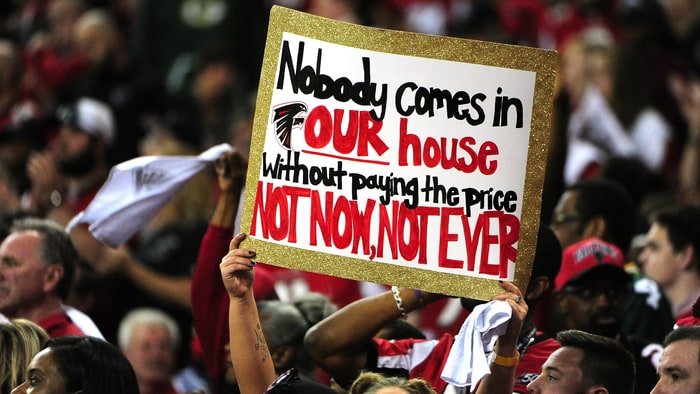

Then there’s the question of who gets to be thought of as a “real” fan in the popular American imagination. Especially in traditional pro sports towns, the personification of a Real Fan is, on average, a middle-class white guy, maybe middle aged or a little bit past it. According to a 2007 survey by Experian Simmons, the league’s fan demographic numbers bear out that stereotype. In the NFL, they’re the guys who paint their faces and brave the awful temperatures of the U.S.’s colder regions in order to cheer on the Packers or the Bears in only sweatshirts, no jackets – their ardent fandom keeps them warm, you see. Atlanta fans, on the other hand, tend to fall along the demographic lines of the city itself, which are far different than its Northern counterparts. Atlanta is a young, incredibly diverse place and the national hub of Black American culture, all of which is particularly well-reflected in the crowds inside the Georgia Dome. It could be that, sometimes, crotchety sports columnists looking to bestow approval on fanbases simply don’t see the people in Atlanta’s stands that they’re used to regarding as real fans.

Besides, what even makes a sports town good? Atlanta has the fans, it has the hunger for long-fought victory, it has the enthusiasm of its players. Atlanta is also one of only three American cities to ever host the Summer Olympics, and it’s the only city ever to welcome the sports world to its doorstep with a transcendently self-parodying parade of fully chrome-plated Chevrolet pickup trucks during an Olympic opening ceremony. Over the past 50 years, the city has built its professional sports history, brick by brick, with plenty of disappointments and setbacks along the way, all characterized by the under-appreciated weirdness that makes Atlanta a singular American city. Things are starting to feel different for Atlanta and its fans, though, and Wilkins, the city’s most iconic athlete, feels it too. “Sometimes, the stars align for you. I just think it’s our time.”

[Source:-Rolling Stone]