The decision to leave the European Union was connected to “resentment” felt by some poorer communities over the North-South divide in the education system, the head of Ofsted has said.

Sir Michael Wilshaw said many people in the more economically deprived areas of England felt “alienated”, including in the classroom where the gap between the North and the South had widened, he said.

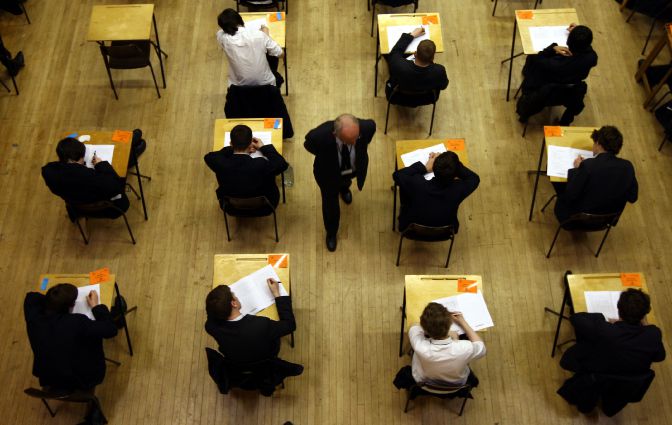

Launching his fifth and final annual Ofsted report into education across the country, Sir Michael said the gulf in standards was particularly felt at secondary school level.

In a wide-ranging critique of the education system, he also said a serious knowledge and skills gap is threatening the country’s competitiveness – particularly in the wake of the vote to leave the European Union, where swathes of traditionally Labour areas in the North of England opted out of the bloc.

Launching his report in Westminster, Sir Michael, in his last official public engagement before stepping down as the watchdog’s chief inspector later this month, said: “It feeds into a sense that somehow they’re not getting a fair crack of the whip.

“They sense that somehow their children are not going to get as great a deal as youngsters in London and the South of England.

“If they sense that their children and young people are going to be denied the opportunities that exist elsewhere, that feeds into a general sense that they’re being neglected.

“It wasn’t just about leaving the European Union and immigration, it was that sense of a disconnection with Westminster.

“If they feel that their needs are being ignored, that their children are not getting the sort of education that others in the South are, then they will feel resentful.”

He said regions that are already less prosperous than the South are in danger of adding a learning deficit to their economic one.

He added: “Recent political history shows what can happen when large parts of the population feel alienated because they feel they are not being dealt with fairly.”

His report showed that the proportion of high achievers in the North and the Midlands who go on to score well at GCSE is lower than in the South, while the proportion of secondary schools in the North and Midlands rated good or outstanding had increased by just 3 percentage points since 2011 – well below the national percentage points increase of 13.

And in Liverpool, half of all secondary schools were rated less than good, compared with three in 10 for Manchester, and just one in 10 for inner London.

But the report also identified success. It showed that, for the sixth year in a row, the proportion of good and outstanding nurseries, pre-schools and childminders has risen and stands at 91%.

The proportion of good and outstanding primary schools has also risen from 69% to 90% in five years, while the reading ability of pupils eligible for free school meals at age seven in 2015 was six percentage points closer to the level of their peers than five years ago.

There are also 1.8 million more pupils in good or outstanding maintained schools than in 2010.

But while he highlighted significant improvements in the country’s nurseries, pre-schools and primary schools, Sir Michael also identified “unabated” pressures on the supply of secondary school teachers.

In a statement referencing official figures released last week, School Standards Minister Nick Gibb said: “Good and outstanding schools now make up 89% of all schools inspected in England, with the proportion of primary and secondary schools in this category continuing to rise in every region of the country, including in the North and the Midlands.

“We want every child to have access to an excellent education, regardless of their background or where they live.

“We know there is more to do, and that’s precisely why we have set out plans to make more good school places available, to more parents, in more parts of the country – including scrapping the ban on new grammar school places, and harnessing the resources and expertise of universities, independent and faith schools.”

[Source:-NEWS & STAR]