The government has announced it is dropping its planned education bill in England, despite it being included in the Queen’s speech. How did that happen?

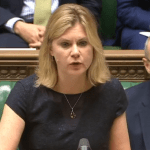

Five months is a long time in education policy. The “education for all” bill, whose provisions were unveiled by the then chancellor George Osborne in his March budget, was quietly ditched on Thursday after some oblique remarks in a written statement by education secretary Justine Greening. It was a miserable end for Nicky Morgan’s legacy as Greening’s predecessor, and the termination of the David Cameron-Michael Gove era of educational policy-making.

Has this got anything to do with grammar schools?

Not directly. In fact, Greening’s statement, ostensibly announcing a new technical and further education bill, was blunt on that point: the current “Schools that work for everyone” consultation remains on track, “including selective places for local areas that want them”. But Labour detects signs that the government is having second thoughts about grammar schools, and in reality the consultation on selection is open until later in November, with a white paper to come early next year – and presumably another education bill will appear after that. Greening’s move is a clearing of the decks: getting rid of the leftovers from the Morgan regime in order to press on with grammar schools and other higher priorities.

What has been lost with the demise of the bill?

Morgan’s signature measure – that all state schools would be forced to become academies by 2022 – had already been rowed back upon. But Greening’s non-announcement does kill off the government’s stated determination to convert all schools into academies, even without a time frame. Greening’s position is that “our focus … is on encouraging schools to convert voluntarily”. Among the provisions to go is one that required all schools in “underperforming” local authorities to become academies. Another is the abolition of statutory places for parent-governors on the boards of maintained schools.

Where does this leave local authorities and the schools they will still be overseeing?

The old bill would effectively have ended the role of local authorities in schools (other than running admissions), placing school improvement in the hands of regional schools commissioners. The government has already budgeted cuts of £600m for local authority schools services next year. Now local authorities have been left in limbo: they still have school-improvement responsibilities, a large number of mainly primary schools to oversee, and no money to do it with. Naturally they are hoping the government will reverse the cuts and allow them to fund school improvement and other educational functions.

So why did the government wait so long to drop the bill?

It took the Department for Education this long to realise how much work it has in front of it. It has only recently completed taking responsibility for higher education from the old Department for Business Innovation and Science, a merger that brought with it another bill to pilot through parliament. Then there was the existing children and social work bill and, as of Thursday, the technical and further education bill, meaning that the DfE had three bills on the go. On top of that the department has the schools consultation – including the thorny issue of grammar schools – to prepare. Then there’s the matter of a promised new schools funding formula, to replace the current byzantine system. It’s a complicated issue that has already been delayed, with Greening last summer promising a DfE response by this autumn. That’s not to mention the department’s daily work of pushing along academies and free schools, and a plethora of other issues.

Why are abrupt changes in policy so common at the moment?

That may have much to do with the post-Brexit change of government, with new ministers and leaders not committed to existing policies and able to ditch those that had proved to be unpopular or inconvenient – even those proposed in a Queen’s speech. Greening has even dropped a 2015 manifesto commitment that would have seen resits for children who underperformed in maths, and reading tests at the end of primary school. A controversial primary school spelling, punctuation and grammar test has also been put on hold after Greening called for the issue of primary school assessment to be retooled.

What other U-turns may be on the way?

The outlook for legislation allowing new grammar schools remains fraught: there appears to be little enthusiasm for it among Conservatives. Even if the SNP stays neutral, any new law could get blocked in the House of Lords. But one policy that could easily be dropped is forced retakes for pupils who fail to gain at least a C in maths and English GCSEs – another Gove-era legacy that is very unpopular among head teachers.

[Source:-The Guardian]