The girls are out on the field. Dribbling a ball, holding a bat, they emerge in the early morning sun, an unstoppable phalanx in bright-coloured jerseys and knee-length socks. Not all are so lucky. Some play barefoot, others in fadedsalwar-kameez. You haven’t heard of them, and it’s likely that most will never step on to a podium, grab sponsorship deals or make breathless headlines. Yet, without being conscious of it, their stories are tiny stepping stones in a long journey of aspiration and desire. Each kick of the ball, each strike of the bat, hits at the heart of patriarchy and a society that continues to scoff: Girls don’t play sport.

Well, these girls do. The daughters of labourers, shopkeepers and factory workers, the drudgery of their routines of homework and tuition, household chores and caring for younger siblings, fetching water and helping mothers does not deter them. For a few hours a day, they are just girls who want to play.

For a country that does not want its girls to play, sportswomen from India are steadily leaving their male counterparts behind. For evidence, you need look no farther than the only two medallists for India at the 2016 Olympics in Rio, both women: Sakshi Malik and P.V. Sindhu. Or look at the last Asian Games, in 2014, where women accounted for almost half of India’s 57 medals; in key disciplines like track and field, women outshone men.

These girls out on the field don’t speak the language of gender and stereotype; they live and experience them. Most face resistance from their families, who can’t understand why they want to play. Many will face huge obstacles, including poor infrastructure and sexual harassment, from India’s officials and coaches. Yet, says Sharda Ugra, senior editor, ESPNcricinfo, “Women will find themselves more and more inspired with each new generation of athletes.”

This is the story of how and where the difficult journeys of our women athletes begin. They include the anonymous girls emerging from the slums and villages of India, from families that do not know the concept of leisure, from the margins of an upwardly mobile aspirational India. As they play on the field, they seem to say: We have dreams. We matter.

*****

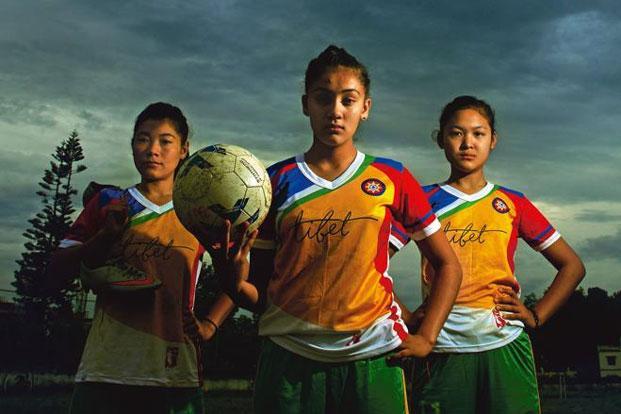

Tibetan girls practising football on the grounds of the Tibetan Nehru Memorial Foundation School in Clement Town, Dehradun. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

Home is a football field, Dehradun

It is 6.30am and the sky is overcast. Clement Town in Dehradun hasn’t woken up completely yet. The shops are closed, the roads empty. Inside the Mindrolling Monastery, things are quiet. Hardly a minute’s walk from the monastery, on the grounds of the Tibetan Nehru Memorial Foundation School, Yangdan Lhamo is getting ready for practice. The 25-year-old midfielder is dressed in the Tibetan gear of green shorts and yellow-and-white jersey.

Coach Gompo Dorjee arrives for practice with two more players in tow, both midfielders—Ngawang Oesto, 15, and Tsering Lhamo, 17. The four kick off the training session with dribbling and heading drills. Centre forward, Tashi Dolma, 24, arrives shortly afterwards and the pack starts 2vs2 drills, with the coach doubling up as the referee. The practice picks up momentum and their smiles turn into stern determination. For that 90-minute session, the four girls transform into fearsome competitors; and football transforms from being a game to a tool of empowerment through which they seek recognition as women, sportspersons and, above all, Tibetans.

For Dolma, it has been a long, excruciating journey, from Tibet to the football ground in Dehradun. Dolma’s parents had to send her to India with an agent in 2003. She was 11 then. “We slept during the day and walked in the nights over the mountains,” she recalls. “Even in the nights, the Chinese army would patrol with guns and flashlights. They would shoot people point blank if they saw them crossing the border. We were lesser than animals for them. That fear of getting caught and shot down doesn’t let me sleep at nights even now.”

Tashi Dolma. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

It took Dolma more than a month to reach Indian land; many of those days, she went without food. She was taken to the Tibetan Children’s Village (TCV) in Dharamsala, Himachal Pradesh, an educational community for destitute Tibetan children in exile.

“I felt alone. I kept crying for days. I could not contact my parents back home for fear of the Chinese government torturing them,” says Dolma.

“I was so overwhelmed that I even tried committing suicide once. I jumped from the TCV building in 2005, the fall breaking my legs,” she recalls.

She could contact her parents only in 2007, a conversation that lasted barely a couple of minutes, one in which her parents asked her not to call again. They feared that the Chinese authorities could intercept the calls and punish them.

Dolma started playing football in 2010 just to be part of a group. It helped her focus her mind elsewhere. Three years later, Cassie Childers, a teacher and footballer from New Jersey, US, who was putting together a Tibetan football team for women, picked her for the national camp, and she has been part of the team since. Childers runs a non-profit called Tibet Women’s Soccer, or TWS.

“TWS is essentially a women’s empowerment programme designed to develop leadership and communication skills and provide a platform for young Tibetan women to express themselves and share their stories with the world,” Childers says.

Tibetan girls in exile in India face several problems. They are brought up in boarding schools without familial support, and suffer from a broad range of issues stemming from their individual situations. In the Tibetan community itself, girls hardly play any role outside their homes. There have been multiple incidents of resistance from within the Tibetan community against the girls playing football. TWS has survived all that, at least for now. It has also survived the challenge of their players being stateless. “They are neither Indian nor Chinese, and Tibet is not generally recognized as a country,” says Childers. “It’s a challenge to travel to international matches because of this.”

TWS helps create grass-roots level teams in Tibetan settlements around India and Nepal. “Each year, we select the most promising players from these teams to join our select team camps, which occur about twice a year. At the select camps, players receive intense training and compete in serious matches with other teams. Last year, we brought our first team to Berlin, Germany, where we met a Chinese team. Those players became the first Tibetan women to represent their country abroad in a sporting match, and the first Tibetan athletes of any sex to meet Chinese athletes in competition,” says Childers.

“That was a historic moment for the girls,” recalls Yangdan, 25, who was part of the seven-member team. “When I met the girls from China and spoke with them in Chinese, they were surprised. They asked me where I was from. When I told them I am from Tibet, they asked me why I was living in India. They were rather shocked to know that Tibet was captured by the Chinese,” Yangdan recalls.

As the tournament progressed, the girls from China and Tibet became friends. They shared stories and clicked selfies.

TWS was started under the aegis of the Tibetan National Sports Association based in Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh. In 2015, Childers severed ties with the association and reorganized TWS as an independent NGO. That’s when the national camp was moved to Clement Town, a small Tibetan settlement on the outskirts of Dehradun, from Dharamsala, and Dorjee was appointed as the head coach. There are currently about 40 girls in the camp.

The girls practise on the grounds of the Tibetan Nehru Memorial Foundation School.

Making a girl’s team is difficult, says Dorjee, the former centre back of the Tibetan men’s national team, who has also worked as the coach at The Doon School.

“Parents are reluctant to send girls to play. There are many prejudices in the local community,” says Dorjee. “But times are changing. Girls who have played in our camps go back to their homes and start training the local girls there.”

As the training session ends on the school ground, Oesto and Tsering rush to change, have a quick breakfast and make a dash for classes. They are fast runners.

Yangdan Lhamo. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

Yangdan Lhamo

Yangdan Lhamo was born in Tibet and sent to India by her parents in 2003. She made the treacherous night trek through mountains, braving hunger, bullets and inclement weather. She went to TCV, where she says she got the chance to study for the first time.

The first time she could speak to her parents after her escape from Tibet was three years later. She doesn’t really remember how she started playing football but says she was around 15 then. Life was never the same again.

“I feel alive on the pitch,” she says. “Whenever I am sad, I play football.” She came to the TWS fold in 2014.

“I often feel like I was robbed of my identity,” she says. “People in Tibet think of us as deserters. People elsewhere mostly don’t know Tibet. So, it makes me proud when people across the world get to know Tibet through us. I think that is why I love football the most.”

How it started

Cassie Childers, 34, visited India for the first time in 2003. Her travels as a young backpacker brought her to Dharamsala, where she first came in contact with the Tibetan refugee community. “I became passionate about both—Tibet’s political cause and women’s status in the Tibetan society—and got the idea to address both problems by starting a soccer programme for girls in the exile community,” Childers writes in an email from New Jersey. And, in 2011, Tibet Women’s Soccer was born. Till date, TWS has introduced more than 5,000 girls to football, she says.

*****

The Saksham Sports Club doesn’t have budgets so the girls play without helmet, pads, even shoes. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

“Who asked you to interfere in our game?”, Delhi

In an overgrown field near Shahbad Dairy’s Sector 28 in New Delhi, a group of girls is playing cricket. It’s not an impressive sight. There is a bat, ball and wickets. But the girls are not wearing helmets, pads, or even—most of them at least—shoes. The fledgling Saksham Sports Club simply does not have the budget and the girls would rather play barefoot than in chappals (slippers).

And yet, under the open skies, the girls are free. Never mind the empty glass bottles of liquor that lie scattered in the grass. Never mind that one of them ended up with a nasty gash on her foot three months ago. Never mind the people who casually walk across the pitch while the match is on. “When I’m playing, I forget everything,” says 15-year-old Kavita Kumari, the captain of the team, who studies in class X in a nearby government school. “I know it’s important to finish my homework and help with the ghar ka kaam(household chores). But here for 2 hours I can forget all of that.”

The Saksham Sports Club got off to a tentative start only in January, although the non-profit, Saksham, that works with marginalized children is 10 years old. The club already has 40-50 children who come to play cricket, badminton, kho-kho and kabaddi, says Santlal, the club’s founder, who uses only one name. “They come to us for help with personal problems or with school homework. But when they’re playing, they forget all their problems,” he says. Moreover, he adds, playing gives the girls a sense of confidence and respect.

Confidence that is on abundant, even reckless, display. When 14-year-old Champa Kumari hits a shot and gets caught by a boy playing cricket on an adjoining pitch, she yells: “Who asked you to interfere in our game?” Her team-members laugh. It’s okay, they tell her. But her aggression is something new, says Santlal. “Before she started playing, she would rarely meet your eye. Now she’s shouting at a boy twice her size,” he laughs.

The daughter of a single mother who works in a factory, Champa is the team’s star. In June, when the team played against Magic Bus, a non-profit that works with marginalized children to create livelihood opportunities, she was, with eight fours and two sixes, declared “man” of the match. “The Magic Bus team had shoes but I played in my chappals,” shrugs Champa.

Champa Kumari, 14, is the daughter of a single mother and is the team’s star.

She has ambitions of playing in the national women’s team some day but for now must juggle schoolwork, homework, cricket and helping with the household chores. “My elder sister cooks, but I wash the utensils,” she explains.

Located in outer Delhi, Shahbad Dairy is dotted with little shops and food carts. But the locality has been in the news for the wrong reasons: 26 rapes reported since January, compared to 37 in 2015.

“No girl feels safe here,” says Santlal. “She gets no respect either at home or from society.”

Persuading the parents in this crime-fraught locality to let their daughters come out to play was not easy. “Parents are scared to let their children out of their sight for too long,” says Pinky, a volunteer with Saksham who also plays cricket. There were other objections:

“It doesn’t look nice for girls to play.”

“They are going to get married anyway, so what is the point of all this khelna-koodna?”

“Who will help with the homework?”

Santlal persisted. In the first joint meeting organized by Saksham between the girls and their parents in January, both sides voiced their concerns. The parents were worried. The girls had aspirations. Both sides wept.

But in the end, the girls won. It was agreed that they would first come to the Saksham office to finish their homework and then go and play.

With a small financial grant from the non-profit, Child Rights and You (CRY), it has been a bit of an uphill battle for the Saksham Sports Club. There is no trainer or coach—the more experienced amongst the girls take on that job. Pinky demonstrates Mahendra Singh Dhoni’s helicopter shot and ensures that everyone gets their turn at the crease—even eight-year-old Pooja, who is the team’s youngest player and is, in the words of Pinky, a natural who is fearless while facing the ball.

“While sport has traditionally been looked at as an activity for boys, we saw the change it brought about in girl children when they were encouraged to take it up,” says Subhendu Bhattacharjee, general manager, development support (north), CRY. Sport, he adds, changes their attitude and their will to continue education. “It has instilled in them a sense of empowerment and they have stood up against child marriage and abuse,” he says.

For now, it’s all hands on deck as the team prepares for a Delhi slum girls tournament in December. “There’s a lot of preparation to be done—arrange funds for the venue, train the girls, get sponsorship. It’s never easy,” says Santlal.

Match over, the girls line up for a quick farewell before they head home where their chores await. “Saksham hamla(attack),” they yell.

Saksham Sports Club founder Santlal. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

Shahbad Dairy, one of Delhi’s worst crime zones

As of June, there was not a single toilet in this slum area, forcing people to use a nearby forest. Between December 2013 and March 2015, 171 children went missing from this forest, according to an RTI reply on missing children filed by Saksham. Of these, five were found dead, 28 girls had been raped and another 17 sexually abused. Murders are frequent. The latest was on 19 August, when a Delhi Police constable was shot dead.

How it started

The son of a driver with the Railways, Santlal’s early learning in the value of education began when his father enrolled him not in the village government school, but in one 2.5km away from home in the village of Guraula, Chitrakoot district, Uttar Pradesh. “I had to walk the distance every day, but my father didn’t want me to study in a school where the teachers never showed up.”

Unsurprisingly, Santlal’s activism as an adult began with education, agitating for greater accountability from schools in his Chitrakoot district. In 2005, he moved to Delhi for a job with the National Conference of Dalit Organizations. But the activism continued, as did his interest in better schools for children. When Saksham was founded in 2006, its first task was to work on issues related to the right to education. By 2012, it had moved to related areas of child protection and health. The Saksham Sports Club began in January.

*****

Jude Felix training the girls from his academy in Bengaluru. Photo: Hemant Mishra/Mint

Courage to face the ball, Bengaluru

It makes me happy,” is Saraswathi Bhandari’s simple, exultant response when I ask her why she likes playing hockey. It’s hard not to believe her or get touched by her infectious joy when she speaks about the sport, which she says has changed her life. Bhandari, now 15, was playing hockey for her school Maria Niketan when she joined the Jude Felix Hockey Academy (JFHA) two years ago. From a shy and diffident girl, she has today morphed into a tenacious player, who her coaches believe can play for the country at the highest level. Despite her lithe frame, she recorded the best scores at the beep test (shuttle sprints) conducted during the girls camp for the annual JFHA tournament in December, where she was also awarded the Most Promising Player of the Tournament. The younger children at school gaze at her with eyes full of unfettered hero worship, something that leaves Bhandari shy. Her father is an office boy, her mother a homemaker, but Bhandari doesn’t let her humble background come in the way of her dreams. “I want to play for my country one day, and it is what my father also wants,” she says. “Now can I go practise?”

Former India hockey captain Jude Felix, together with former internationals like Shanmugham P., started JFHA with the objective of developing the sport among underprivileged children. The academy is run solely on donations, the model developed primarily on volunteer participation; the number of volunteers has gone up to more than 40 today from two in 2009.

While the boys started joining in large numbers, getting the girls proved to be a more formidable task.

“At one time, hockey was very popular among girls, but gradually the interest waned,” says Felix. The reason? Lack of a comprehensive pan-India programme for girls that was exacerbated by the fact that there weren’t enough school tournaments. One of the first girls to start playing at JFHA was Meryl Deena Pereira. She joined the academy in 2010, and today she is one of the coaches for the girls’ team.

“When I joined, there were only two of us,” recollects Pereira, 28. “Today we have a proper team.” In January 2015, the Employee Foundation of FibreLink, a software company, sponsored a girls’ programme. Thirteen girls joined and slowly word spread. At that time, Pereira had started teaching at the Little Angels Public School, RT Nagar. Seeing their teacher play hockey, many girls started showing interest.

Now, around 40 girls from the Maria Niketan High School, Little Angels Public School and the local community are part of the girl’s programme.

“To have 40 girls itself is a winning thing,” says Felix, smiling. As we speak, the girls slowly start entering the grounds. Their cheery cries of “good morning, coach” ring through the cool Bengaluru air as they get into their kit and start their warm-up session. The training happens every day—except Monday which is a rest day—from 6-8.30am on weekdays and 6.30-9am on weekends.

Coaching at the JFHA is as professional as it gets, with multiple former state- and national-level players helping out. Not only are the girls taken through the necessary fitness drills, there are also separate coaches for the various aspects of the game: a goalkeeping coach, a coach who focuses on the midfield, one for the forwards. And it’s not just about the hockey. Volunteers like Josephine Sequeira, a former state-level player, talk to the girls about hygiene, women’s health issues and how to carry themselves and socialize. An education they might not necessarily get elsewhere. Gender equality is a key focus at the academy: The girls often train with the boys and even play matches with them.

The biggest change that the coaches see in the girls is a sense of discipline and self-confidence. “They come on time, take care of their diet and have improved fitness,” says Pereira. “They listen to people, ask me what to do, which is really important. Hockey is a rash sport, but they develop the courage to face the ball even if it hits them on the body.”

As the girls start playing a mock game, I see a few parents standing on the sidelines cheering them on. Parental support has been crucial in making the programme gather momentum. “The first thing we do is talk to the parents about the programme,” says Shanmugham. “It’s a question of self-realization. The parents see the positive changes in their child once she goes back home; the major impact happens there. So why would anyone stop them from playing the sport? It will be a generational change.”

“I want my daughter to be carefree and follow her dreams,” says C. James, 59, a driver, who drops his daughter, Esther, to practice and picks her up.

“The only way she can learn about the world is if she steps out of the four walls of the house.” His gaunt face lights up as he watches Esther line up to take a shot at the goal. Esther, 14, can barely contain her excitement when I ask her what she would like to do in the future. Words tumbling, she says she would like to play for the country and repay her parents for all their support.

Vinisha M.

The 14-year-old hockey enthusiast travels all the way from RT Nagar to the Jude Felix Hockey Academy, a distance of nearly 10km. Her father, an auto driver, ferries her friends and her to and fro every time they go for practice.

How it started

The JFHA, brainchild of former India coach, captain and Olympian Jude Felix, began operations in 2009. Felix was at the St Mary’s Orphanage in December 2008 when a friend mentioned to the orphanage secretary that Felix had plans to start a hockey academy.

“One thing led to another,” Felix recollects, “and here we are today.”

The first project was in partnership with the boys from the orphanage. In the early days, thanks to the association with the orphanage, the JFHA also got access to a playing ground, attached to the Maria Niketan school, and a small room for an administrative office. When they started off, the boys would play barefoot. Today, the children are provided a complete kit and all the playing equipment by the JFHA. The old St Mary’s Bakery next to the ground has been converted into a mini-gym, a kitchen with a refrigerator, and a storehouse for all the equipment and clothes. Hockey sticks are bought in bulk from Jalandhar, and socks from Kolkata. A donated washing machine is used for laundry.

*****

Shaktheeshwari J. volunteers to coach other Dalit children over the weekends. Photo: Hemant Mishra/Mint

Play football, stay in school, Chennai

The road leading to the Mullai Nagar playground in Vyasarpadi, Chennai, is interpersed with piles of trash and murky runnels of sewage. Long rows of housing board flats, tinselled with straggling cables, loom across it, their once-bright exteriors now faded and peeling. A few men in grimy clothes lurch out of a local liquor store as a herd of goats passes.

A lone floodlight at the corner of the playground casts its glow across the bright green turf field on which children in neon jerseys, shorts and knee-length socks (some mismatched) are playing a game of football, keenly observed by their coach, N. Thangaraj, “These children here have grown up in the slums of this area,” explains Thangaraj, co-founder of the Slum Children Sports Talent and Educational Development Society (SCSTEDS ) that aims to use football as a tool to help the children of this area. Most of them belong to the Dalit community and are the offspring of daily-wage workers, he adds.

Shaktheeshwari J., 24, was once one of them. Dressed in a purple salwar-kameez—“I came directly from work so I couldn’t wear my football jersey,” she explains—the petite young lady with a winning smile now volunteers to coach these children over the weekends. Shaktheeshwari, an apprentice at the Madras high court, has just started practising law. “I don’t get paid for this but I need the experience,” she says. She also works temporarily at a local ambulance helpline at nights to help pay the bills at home.

Her days are long and tiring; “I get time to sleep only a couple of hours a day,” she says, wryly. “I have gotten used to it.”

Despite her hectic schedule, however, she finds time for her greatest passion—football. It is what has made her what she is today, she says.

“My father used to drink and he abandoned us when I was very young,” says Shaktheeshwari. One of five children, she spent her childhood flitting between school and the local fish market where she worked part-time, gutting and cleaning fish. The sight of children playing in her school grounds every day piqued her interest and she decided to learn the sport too. It was not easy, “Vyasarpadi is a place where women aren’t allowed to walk about freely,” she says, adding, “Also, there was a stigma attached to girls playing sport here.” For girls, even something as basic as wearing shorts to play is a problem, adds N. Umapathy, the other founder of SCSTEDS and Thangaraj’s younger brother.

“We are in the centre of the city, very close to areas of economic activity like the secretariat and beach. But we have barely developed,” says Umapathy, who grew up in these very slums and now holds a day job as an income-tax officer. According to him, most children in these slums have limited access to education. “We need proper education—the education we currently get is not good enough,” he says, pointing out that it becomes hard to mainstream children who pass out of this system. “They don’t get employment and become anti-social elements,” he says.

Football helped him get this job (through the sports quota), he says, “It made me understand the benefit of it and I wanted to do something that would pass this same benefit to the children of this slum.” He began teaching children football in 1997.

A lot of the children he coached ended up getting admission to colleges on the sports quota—it is often impossible to get a degree otherwise.

“I got admission into college due to the sports quota,” says Shaktheeshwari, who now holds degrees in both science and law.

“The main thing football taught me was courage,” believes Shaktheeshwari, adding that the game empowers women because it makes them think and question prevailing systems. “All my sisters got married very young,” she says. “I may have gone that way too but because of my exposure I know that there are other options for a woman.” Shaktheeshwari has travelled widely with football, playing matches for both the district and the state.

She has even represented India at the Homeless World Cup in France in 2011. “I went all the way to the top of the Eiffel Tower and saw the city spread out before me,” she smiles.

Despite all that she has achieved, she has not been able to shake off the twin demons of poverty and oppression that cling like a burr. She continues to live in a slum and struggles to eke out a living. The single-roomed tin-shack that houses the girl and her family is swelteringly hot and crammed with their few material possessions: clothes flung across a heavily burdened clothes line; a refrigerator whose top is covered with cooking utensils, oil and masalas; a single Godrej cupboard under which four kittens nestle.

Shaktheeshwari’s mother Krishnaveni, who works in the housekeeping division of a local hotel, is cooking dinner when we arrive and a few pieces of fish are basting on a pan, filling the room with their distinctive odour. Turning off the burner beneath the fish, Krishnaveni offers a tired smile and remarks, “Of course I am proud of my daughter and what she has accomplished. She has gone to places we have never even heard of due to football.”

However, she also believes that the game on its own is not enough: “It is good for a girl to play a sport but it is more important that she gets a job and becomes financially independent.”

Vyasarpadi, neglected

Located in the gritty northern part of the city, Vyasarpadi is populated by the economically, socially and historically marginalized. It was home to some of the most notorious gangsters of this region during the 1990s. Gang wars were commonplace, as were shootings, assassinations and police encounters; and reports of heads being lopped off and people being stabbed here often trickled into the mainstream media. Much has changed, of course, but the people of north Chennai still claim stepmotherly treatment, insisting they are constantly neglected and passed over by political leaders and welfare committees.

How it started

SCSTEDS was formally registered in 2000, though Thangaraj and Umapathy had started coaching in 1997.

“We are using football to drive education—that is the main goal,” Umapathy says. SCSTEDS partnered with CRY in 2006 to further drive this cause. “Football is played here every morning and evening seven days a week for the past 16-odd years,” he says, adding that the school dropout rate in the locality has reduced considerably, thanks to the sport.

[Source:-Livemint]