Summary

Introduction

As a consequence of the pandemic, social media is becoming the platform of choice for public opinions, perceptions, and attitudes towards various events or public health policies regarding COVID-19.

Social media has become a pivotal communication tool for governments, organisations, and universities to disseminate crucial information to the public. Numerous studies have already used social media data to help to identify and detect outbreaks of infectious diseases and to interpret public attitudes, behaviours, and perceptions.

,

,

,

Social media, particularly Twitter, can be used to explore multiple facets of public health research. A systematic review identified six categories of Twitter use for health research, namely content analysis, surveillance, engagement, recruitment, as part of an intervention, and network analysis of Twitter users.

However, this review included only broader research terms, such as health, medicine, or disease, by use of Twitter data and did not focus on specific disease topics, such as COVID-19. Another article analysed tweets on COVID-19 and identified 12 topics that were categorised into four main themes: the origin, source, effects on individuals and countries, and methods of decreasing the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

In this study, data were not available for tweets that were related to COVID-19 before February, 2020, thereby missing the initial part of the epidemic, and the data for tweets were limited to between Feb 2 and March 15, 2020.

Therefore, social media has a crucial role in people’s perception of disease exposure, resultant decision making, and risk behaviours.

,

As information on social media is generated by users, such information can be subjective or inaccurate, and frequently includes misinformation and conspiracy theories.

Hence, it is imperative that accurate and timely information is disseminated to the general public about emerging threats, such as SARS-CoV-2. A systematic review explored the major approaches that were used in published research on social media and emerging infectious diseases.

The review identified three major approaches: assessment of the public’s interest in, and responses to, emerging infectious diseases; examination of organisations’ use of social media in communicating emerging infectious diseases; and evaluation of the accuracy of medical information that is related to emerging infectious diseases on social media. However, this review did not focus on studies that used social media data to track and predict outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases.

Methods

Overview

and Levac and colleagues.

We followed the five-step scoping review protocol and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews.

Data Sources

Screening procedure

Braun and Clark’s thematic analysis method was used and involved searching for the text that matched the identified predictors (ie, codes) from the quantitative analysis and discovering emergent codes that were relevant to either the study objective or identified in the relevant literature review.

Finally, we categorised the codes into main themes. These codes and themes were compared and clarified by S-FT, ZAB, and YY to draw conclusions around the main themes. S-FT is fluent in English and Mandarin. The secondary reviewer (ZAB) is fluent in English, and the tertiary reviewer and domain expert (YY and HC) are both fluent in English and Mandarin. Any discrepancies among reviewers were discussed with the research team to reach consensus.

Results

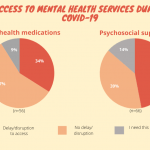

Themes were identified through reviewers’ consensus based on our modified SPHERE framework. We identified six themes: infodemics, public attitudes, mental health, detecting or predicting COVID-19 cases, government responses, and quality of health information in prevention education videos.